Last year I wrote “Leaving London, Arriving in Albion” an article on the future of steampunk for Chris Garcia’s Exhibition Hall. In it, I imagined an airship taking us on a tour of global steampunk, flying across the Atlantic to the Americas with weird westerns, then across the Pacific to Asia for the steampunk spawned by anime, and then beyond this world to alternate realities where magic and science blend to create fantastic secondary worlds filled with radical technofantasy.

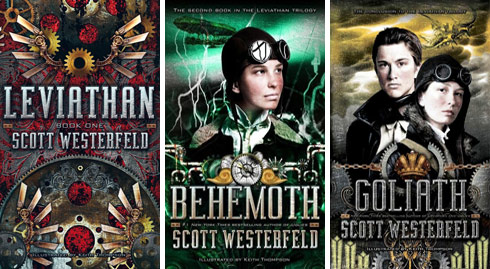

While reading Goliath, the final book of Scott Westerfeld’s steampunk trilogy, I realized that my hypothetical airship is the airship Leviathan. This isn’t to say I “predicted” the Leviathan trilogy. The first book had been released the previous fall; instead, I’d say Westerfeld’s vision fulfilled what was on the horizon of steampunk in 2009.

Leviathan was released in the same month as another auspicious steampunk novel, Boneshaker by Cherie Priest. Both had powerful marketing campaigns, and both gave birth to popular steampunk series. But whereas Priest’s storylines have stayed put in America, Westerfeld’s have roamed the globe, daring to steampunk a “range of cultures and technologies,” as Ay-leen the Peacemaker put it in her review of Goliath.

While some publishing houses just getting into the steampunk game are apparently rejecting manuscripts that take place outside London, Westerfeld is wrapping up a series that left London in the first volume, and never returns. Departing London, Leviathan heads south to crash land in the Swiss Alps; Behemoth finds our heroes in Constantinople, where their travels provide them with more than a change of scenery: it provides the hero and heroine with a change of perspective:

“Is-tan-bul,” Doctor Barlow said, tapping her riding crop against her boot once for each syllable. “That’s what we must remember to call this city. Otherwise we shall annoy the locals.”

“Istanbul?” Newkirk frowned. “But it’s ‘Constantinople’ on all the maps.”

“On our maps it is,” the lady boffin said. “We use that name to honor Constantine, the Christian emperor who founded the city. But the residents have called it Istanbul since 1453.”

“They changed the name four hundred-odd years ago?” Deryn turned back to the window. “Maybe it’s time to fix our barking maps.” (99-100)

Learning that the map is not territory is a major theme in Behemoth, and then driven home repeatedly in Goliath as the Leviathan travels to Russia, Japan, the United States, and Mexico: ethnocentricities on both sides of the escalating war are brought into conflict, mirroring the large-scale national clashes. The Great War is writ small in the adventures of Deryn Sharpe, a Scottish girl masquerading as a boy in the British Air Service, and Prince Aleksander, exiled heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. They are each representatives of their respective nations’ technological ideologies: Deryn is a Darwinist, and Alek is a Klanker.

It is in his imagining of these two technological approaches that Westerfeld’s globe-spanning steampunk departs more than London. The vehicles which span the globe are departures of another kind, bringing a whole new approach to Industrial-era technofantasy. While the series begins with conventional steampunk tech as exemplified by the Klanker Stormwalker, effectively a steampunked AT-ST, the Darwinist fabricated beasts, most notably the massive ecosystem of the whale-as-airship Leviathan, were something new to steampunk, while maintaining a link to the nineteenth century’s interest in Darwin’s new theories. There may have been nods to it in the past, but none rendered on the scale Westerfeld engages in.

What was even more brilliant is that the ecosystem of the Leviathan became an ongoing metaphor for the novels’ crises. The Great War isn’t framed as something caused by a single event, but rather a massive wave that broke with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. Alek accordingly sees the War as his fault, and believes it is his destiny to bring peace. In Goliath, Deryn explains that the War “would have gone on, year after bloody year, no matter what you did.” As with the Leviathan, everything is connected, but not in a way that finds history being changed by one person’s actions. Instead, it requires community. As Deryn reflects, “every time one of them had fallen—in the snows of the Alps, in Istanbul, on the stormy topside, in that dusty canyon—the other had been there to pick them up.”

Deryn and Alek’s relationship becomes suggestive of the solution to the war a putting aside of techno-ideological differences to work toward the common goal of peace. Many young adult novels contain romance, but few weave that romance into the fabric of the story’s themes; many steampunk novels contain delightful technofantasy, but few weave that technofantasy into the fabric of the story’s themes. Westerfeld has done both, weaving the technofantasy of an airship ecosystem with an impossible romance between an exiled prince and a girl masquerading as a boy, and then tying all of that to the way a person’s actions affect the greater movements of history. Like the life threads of his hybrid biotechnology, Westerfeld blends these elements to produce a masterwork of fiction. As the enigmatic Dr. Barlow says in the first book, introducing the theme that will resonate through the rest of the series:

“You see, my grandfather’s true realization was this: If you remove one element—the cats, the mice, the bees, the flowers—the entire web is disrupted. An archduke and his wife are murdered, and all of Europe goes to war. A missing piece can be very bad for the puzzle, whether in the natural world, or politics, or here in the belly of an airship.”

It’s apt then, that Westerfeld takes us around the world in his biotech airship, since this is a timely message for a global village: would that we could put aside our own Klanker or Darwinist ideals, metaphorically speaking, to cross the boundaries that divide, to clasp hands and pick each other up. As Alek’s mentor says to him when he expresses concern for the crashed airship in the Swiss Alps: “May I remind you that they’re the enemy, Alek?” The young prince’s reply is laudable: he crosses the glacier, and brings assistance.

“We save each other,” Deryn says in Goliath. “That’s how it works.”

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.